Please Save My Boy! Please! Please!

Phan Vũ

The sun was high on the top of the green bamboo bushes. The hot air was dwindling as the fresh suave new-rice-smelling wind coming from the rice fields delighted Lâm Thúy’s hardworking villagers, expecting an abundant rice crop. Lâm Thúy was a prosperous village, surrounded by a rampant bamboo rampart, about 20 miles in the North-West of Quảng Tri province. Chi, 19, an agile, healthy country girl with gleaming brown eyes on a pretty, smooth skin face, started closing her mother’s Goods for Less sheet metal stall. She was arranging all the merchandises in her wooden iron-framed cart, fixed on three motorcycle wheels. She looked up from the cart, catching the admiring look of a tanned, young and robust man. She was pleasingly attracted by his light brown, smiling eyes. She looked down, flushed with shyness, trying to recover her calm countenance and accusing herself of the audacity of staring squarely at an unknown young man.

“Miss, here’re the items I need,” Hồng said, handing her the shopping list. Still embarrassed, she picked up two cans of condensed Nestlé milk.

“I want only one,” Hồng said, smiling.

“Sorry,” she replied, more confused. She had the vision that her merchandises were moving. She did not know where coffee, tea, and black beans were. Carefully and slowly, she filled out the list. She calculated the bill mentally and he paid the amount. She felt the young man’s hand’s warmth on the paper notes he handed to her. He said good-bye and left. She did not dare to look up, sensing his stare at her. But eventually she could not help lifting her eyes towards him and she met his affectionate face. Involuntarily she smiled back at him, a surge of indistinct joy expanding through her body. She stood still for a while, enjoying that feeling, primary, unexpected and strange to her.

Entering her house, saying hello to her mother, and putting away her cart in the back room, she sang Qu’est-ce sera sera, What will be will be. Her mother followed her beloved daughter’s demeanor, perceiving the happy secret developing in her nineteen-year-old girl’s soul.

“What’s up, honey?”

“Nothing, Mom.”

“OK. But I know what it is,” the mother said, chuckling enigmatically. The girl stopped singing and pondered, how did she know? Only a guess, never mind.

“Oh, Mom,” she said.

Day after day, she was restless: hope following despair like rain after sunshine in the autumn season. She was eager to meet him again. She forgot his image at rush hours, busy receiving merchandise orders or serving a long line of customers. But in the evening, after dinner, sitting with her mother, she felt lonely. She remembered his last look and his head turning back to her while his body was disappearing behind a long pendant eight-hand cluster of bananas at a corner of the streets.

“Mom, I’m sleepy. I’m going to bed. I’ve locked the doors and windows and I’ve put out the stove. Good night, mama,” she said with a slight sigh.

One Sunday, late in the afternoon, Chi and her mother were sitting on the verandah, sipping hot tea and eating cakes as dessert. The smell of fragrant jasmine pervaded the air around them. A breeze moved the bright red leaves at the tips of the poinsettia branches. A woman about sixty, well dressed in dark blue silk áo dài, black pants, and wearing black nylon sandals, stopped outside the wooden yard gate. Chi got up and answered the gate.

“Good evening, Aunt,” Chi said.

“Hello. Is your mom home?” the lady asked.

“Yes, she is.” Chi looked at the lady’s round, smooth-skinned face with lively black eyes. The woman seemed a little bit familiar to her. Her hair was well combed, curled and tied into a tennis-ball-sized knot just above her nape. Chi took the lady into the sitting room and invited her to have a seat.

“My mom will be with you shortly,” she said.

From the kitchen, Chi brought two cups of fragrant hot tea while her mother came out in a black áo dài.

“Good evening, Hong’s mother,” she said. “What wind’s brought you here?” Hearing the name Hong, Chi’s face reddened. She knew what it was about. Putting down the tea on the table, Chi slipped into her room. She peeped through the curtain, listening to their conversation, her heart pounding. The two women talked about the coming rice crop. They agreed that it would be more abundant than the last year’s because of the favorable weather, the development of the communal irrigation, and the sufficient supply of fertilizer. They talked about the business in the market and the relatively good security of Lâm Thủy village.

“Chi’s mother,” the visitor said, after sipping some tea. “You know that I’m a widow. I’ve worked hard to raise and educate my son to be a good man.”

“Well, my status isn’t different from yours,” Chi’s mother said. “Since my husband has passed away, my only happiness is my daughter Chi. I’ve raised her and taught her how to do the business and how to behave as a good Vietnamese girl.”

Hồng’s mother continued, “For months, my son and I have watched Chi during her business work. We are very pleased with Chi. I’ve come here tonight to express my will of uniting our two families. My son has fallen in love with Chi and he wants to ask for Chi’s hand.”

“Well, this is a serious matter,” Chi’s mother carefully replied after a long moment of thinking in silence. “I must talk with my daughter about it…Please come back in about three weeks.” The visitor finished her tea, got to her feet, and the host walked her to the yard gate. Chi stole out of the room and hid behind a wooden column. The two ladies stopped in the middle of the yard, looking up to the blue starry sky, the crescent moon flying across patched white clouds.

“What a beautiful night!” Hồng’s mother said.

“Yes, it is,” Chi’s mother replied, holding the visitor’s hands. The friendly gesture seemed to assure Hồng’s mother that the answer would be positive. She smiled broadly, looking at Chi’s mother in a grateful manner.

“I smell grapefruit. Do you have any grapefruit trees?”

“Yes, my husband planted two of them when he married me. They are twenty years old now. This year, each of them has about two dozens of fruits. This kind is very sweet and juicy.”

Hồng’s mother stepped out of the yard gate after saying good-bye. Chi’s mother closed and locked the gate. Chi saw her mother slowly coming to the house, with a thoughtful countenance. Seeing her daughter in the sitting room, she asked, “You’ve heard the conversation, haven’t you?”

“Yes, I have, Mom.”

She sat down in an armchair, sighing. The round electric forty-watt bulb, hanging down without a lamp shade, shed all over the room a dim yellow light, reflecting two black moving shadows, one old and one young, on the wall as the wind was blowing in from the garden.

“What do you think about it, my dear?” her mother asked. “Do you know him?”

The daughter kept silence. Then she said, “Yes, I do, but not much. The house will be quieter. You’ll be lonelier, Mom.”

“Honey, your happiness matters. I’ll be okay…. I feel sleepy. I go to bed.” She let out a long sigh, pleased that at least her daughter would be settled down well as her husband had told her his wishes about their daughter before he passed away. She had known Hồng’s family for many years since the day his father was still alive. Hồng was a good young man and his mother was a devoted wife. It was a happy honorable family.

After a month, the two women met again and signed an agreement in the presence of some uncles and aunts of the two families, concerning the jewels for the bride, the quantity of areca-nuts, betel leaves, cans of tea, bottles of wine, and the engagement and the wedding dates. They made plans for the wedding ceremonies and reception.

The next day Chi had the house painted white, doors and windows blue, the yard tidied, the fence fixed, and the yard gate replaced by an iron one. One sunny day Chi and her mother took the bus to Quang Tri City to buy new shoes and fabric for her bridal áo dài.

On the engagement day the two families gathered for the first time for a party. After a round of lotus-smelling tea, Hồng’s mother introduced to the bride’s family her brothers and their wives, her sister and her husband, and her husband’s brother and his wife. Then Chi’s mother presented her younger sister and her husband to the groom’s family. They shook hands and sat down at the party table, the two family members facing each other.

At the party table, Hồng timidly ate his food that Chi’s mother tenderly handed to him, an affectionate gesture from a future mother-in-law. Occasionally, he furtively looked at the kitchen, searching for Chi’s shadow while Chi was watching him behind the curtain from her room window. Secretly she smiled, contented at her charming prince with his courteous gentle manners.

In the afternoon, Chi divided areca-nuts and betel leaves into parts, each part containing two green golf-ball-like areca-nuts, two betel leaves, and a can of tea, packed in red transparent paper. She was going to offer these packs as an engagement announcement to Chi’s relatives, neighbors, and acquaintances around Lâm Thủy market. Everyone smiled at her, saying “congratulations” or “a perfect couple.” She felt very happy.

Their first date was on the fifteenth of lunar August, the autumn full moon night. With her mother’s permission, Chi and her fiancé went to the village pagoda square, participating in the autumn lantern procession organized by the Village Council to the villagers’ children. When they arrived, the square was crowded with noisy children and their parents, each child holding a lantern in one hand and some candles in another. Chi and her fiancé sat on a cement bench, looking at those excited children, busy lighting the lantern candles. Suddenly the loudspeakers announced the arrival of the mayor. He shook hands with the organizers. Then everyone stood up under the three-red-striped yellow flag and in front of a long table piled up with brown square cakes, white round ones, and two five-gallon cans of tea, surrounded with paper cups. The children lined up into rows, facing the table.

Everybody kept silence for the flag salute. The mayor gave a short speech about the meaning of the Children’s Autumn holiday. Then the children slowly paraded before the Mayor and the organization committee, who scored the lanterns. Each child holding his/her lantern with a number sticker passed by the table, picked up a brown salted cake, a white sweet one, and a cup of tea. They ate the cakes and drank tea while listening to the mid-autumn moon music. Very excited, Chi talked spontaneously to her fiancé, forgetting her shyness and commenting which lantern would be awarded. Taking advantage of her high spirit, Hồng held her hand that, by instinct, she withdrew jerkily.

“Look at that lantern. It’s very cute,” she said. “It’s a big, red, blue and white rooster with a red jagged comb, and a long long blue white tail. Hồng, I think that boy will be the winner.”

“I think so, too, honey,” he replied, putting his hand on hers. She turned away from him, smiling, but she didn’t withdraw her hand. He was pleased, sensing a change of attitude in her heart. She became troubled by his warmth inching slowly from her hand through her shoulder to her heart, which began pounding and stirring up with a pleasing feeling.

“Chi, honey!” he called her.

“Yes?” she felt his hand softly caressing hers and then going up to her shoulder.

“I love you,” he said.

“Thank you, Hồng,” she answered. “I love you, too.”

The yellow flag was tossing up and down, to and fro. The fresh air was blowing the sweet smell of lotus flowers from the pond, moving the lanterns around the bamboo handles. A sudden shout burst out when a fish-shaped lantern caught fire, the flame creeping its lateral fins, its spinous dorsal fin, its eyes, then its mouth, and finally licking the hanging thread. The boy threw the handle away and jumped up to his father, embracing him, crying, and jerking up and down.

“What a pity!” Chi said.

“Yes. Poor boy.” Hồng sympathized.

The girl sitting beside Chi was eating her salted cake. She said, “Mom, look at these watermelon seeds. They taste crispy and have a fragrant smell… This is an almond nut. It’s fatty and crispy.”

“Oh, really?” her mother said.

“What’s this, mummy?”

“Salted duck egg yolk.”

“The taste is strange to me, mom.” The girl said. “Have a bite, mom. I can’t say what it is like.”

“Yes, it tastes fatty, tender, and soft.” The little girl started eating the white sweet cake. She asked, “Have a bite, papa?”

“No, thanks, my dear. Enjoy it.”

“It tastes better than chewing gum, daddy.”

“Sure, it does. It’s made of sugar, green mung bean, almond, watermelon seeds, and vanilla,” her father answered.

Moved by the nice conversation of the happy family, Chi leaned against her fiancé, watching the round bright full moon flying in the opposite direction of the small moving patchy clouds in the azure sky. “Whoop. Whoop.” A big black trout jumped off the pond water, making a series of circles and waves that expanded far far away. Chi did not hear the sound of her fiancé’s kiss on her cheek, but she only felt its touch. That was the first kiss, she received. It opened her new life. More intimate, Chi and Hồng walked side by side, hand in hand, talking about the children’s autumn moon procession, the cakes they ate, the tea they drank, breathing the dewy air, touching the dew drop on the leaves, and observing the moving atmosphere. He kissed her on her wet soft lips in front of her yard gate.

Chi and Hồng’s wedding was scheduled on Christmas Day 1968. She was 19 and he, 20. Chi was told that day was fortunate to their ages. Under her supervision, the house had been wonderfully decorated with the help of her cousins and friends. A large, avocado tent was set up over the front yard under which four round tables were covered with white cloth, each table surrounded with ten chaises. Baskets of assorted flowers and green coconut leaves were hung along the windows and wall corners.

In the living room, above the altar were three pictures, one of which was Chi’s grandpa, another, her grandma and the last one, her father. On the altar there was a vase of red roses, yellow chrysanthemums, and white lilies, two shining candlesticks, an incense burner, and a large dish of yellow bananas, red apples, black grapes, and white milk-fruits.

Chi woke up early on the wedding day, took a quick shower and then she was ready for the make-up. The bride’s family gathered together, waiting for the groom’s family’s arrival. Chi saw that as soon as the eldest of the groom’s family approached the bride’s house yard gate, two long strings of red fireworks went off, producing a striking display of light and a quick-firing noises scattered with some loud explosions. The strings of fireworks jumped up and down, from side to side, among the children’s joyful shouts and yells, both hands over their ears. Gusts of flying smoke mixed with red torn paper and the thick smell of TNT powder hindered momentarily the respiration of the surrounding people.

The groom’s family members entered the bride’s house, the eldest man in a black ao dai and a black headdress leading the line, followed by eight young men carrying eight round, red-cloth-covered boxes, then the groom, his mother and relatives. Eight young girls in golden áo dài, headdresses and white pants received these eight boxes and put them on the long, white-cloth-covered table. Chi’s mother invited her guests to have seats. Chi’s friends and cousins served them hot jasmine-smelling tea, green Mung bean cookies, glutinous rice cakes and sweets.

After rounds of talking, laughing, drinking and eating, Hong’s uncle got to his feet and said, “This is a beautiful fortunate day, today. According to the agreement between the two families, we’ve brought two big red wedding candles, a gold one-carat diamond wedding ring, two .75-carat diamond earrings and a gold ruby pendant as jewelry, two bottles of Finest French Ascott Brandy, sticky rice boiled with green mung beans, and a twenty-pound barbecued suckling-pig. Please, the Bride’s family accept them.”

“Thank you,” Chi heard her mother say. Then her mother came inside while the candles were put up on the candlesticks and lit. Everybody looked at the door, silent and waiting. The white curtain moving to one side, the beautiful smiling bride walked out, escorted by her mother. The groom stared at her lovingly without a wink. The room seemed brighter, fresher and livelier. The two mothers stepped forward to the bride and put the jewels on her. Then the bride and the groom bowed to the altar, Chi’s mother, her aunt, and uncle. Finally they bowed to each other.

The marriage procession moved slowly out of the house, the eldest man leading the way, followed by young men bringing back boxes and by two strong people carrying the bride’s chest. Wearing new expensive clothes, relatives and friends of both families ended the procession, talking and laughing. Flanked on both sides by two men holding two big flat yellow parasols hovering over the newly-weds, Chi and Hong walked among the women whose golden or white silk ao dai flaps were flying, sometimes too high to show their ripe round buttocks.

The arrival of the wedding procession to the groom’s house was welcomed by a long noisy firing of fireworks. While the guests got in line, waiting to sign the pink wedding book and drop their gift envelopes into the box on the table, the groom walked his bride onto their room. The guests were invited to have seats, according to their relationship or acquaintance or social ranks under a big tent of dark brown tarpaulin.

When the mayor of the village and Hong’s local defense chief arrived, the party began with the hors-d’oeuvre composed of boiled sausage, pig ears and quail eggs. The wedding guests praised the five-course menu of delicious foods, prepared by a famous chef. The more they enjoyed good foods, the more they drank rice wine, and the noisier the party was. Alcohol smell mingled with the odors of barbecued pork, fried onion and garlic, and the human sweat made Chi feel tired, sleepy and hungry. Finally one by one, the guests said congratulations or thank you to Hong and Chi. They stepped out of the gate happily under the red and golden wedding banner.

The reception was over. Chi sadly saw her mother off at the gate. Imagining her lonely mother in a quiet house, she felt acute pains surging in her soul, the first separation with her father and now the second with her mother. She couldn’t retain her hot tears.

“You told your cousins to stay with mother tonight, didn’t you?” Hong asked his wife. “I think she’ll be all right.” Chi nodded in silence.

Two days after their wedding, Chi and Hong took the bus to Quang Tri City where they bought train tickets to Lăng Cô Island, fifty miles south of Hue. They got off the train at Truồi railroad station built right at the bottom of Hải Vân Pass, Sea Cloud Pass. Lăng Cô was a small fisherman island, about one kilometer off the shore and connected to the mainland by a rocky strait. The population was about thirty peaceful families. A tricycle took them to an inn near the wharf. The inn owner served them three meals a day with rice and seafood. The seafood was very fresh and tasty. But the rice was not so good and fragrant as the one they grew. Chi and Hong passed their honeymoon happily, swimming in the sea, walking, chasing along the shore and sleeping in the fresh salty air from the Pacific Ocean under coconut trees. They explored the forest along the bottom of the Sea Cloud Pass, following the rattan plants trailing from trees to trees about forty yards in length. They picked Xâm Xâm leaves, which they ground and squeezed the juice out of to make a jelly.

Lying and embracing each other in the golden shaking moonlight on the beach, they thought they were born to live together and for each other. They forgot the time. When they saw fishermen‘s boats, one by one, sailing out, up up, down down, far and farther toward the indistinct rosy horizon, starting a new fish-catching day, they came back to the inn. Two weeks came to an end. They left the island in regret.

The two mothers were very pleased to see Chi and Hong coming back home after their honeymoon trip. The young couple was happier, healthier and tanner. They resumed their work, Chi helping her mother with the business, which was growing, and Hong serving as a local militia as well as taking care of his rice fields.

Her husband took her to their rice fields. The annual rice crop was partly used for the family’s food and the rest was sold for the purchase of fertilizer and for the family’s expenses. Besides the duty at the military position, Hong came home, tidying the garden and planting more fruit trees. The villagers lived abundantly and prosperously. The security in the village was strict, thanks to the great effort of the mayor and the vigilant local paramilitary soldiers. There were no Communist cells planted in the village.

The two families were expecting the birth of the baby, the precious gem of the family. A beautiful boy was a joy to the young couple, their mothers, their neighbors, and their friends. The first month birthday party gathered relatives and friends. The boy had a lot of toys and money.

As Tet came near, villagers worked hard in the rice fields surrounding the village. Chi and Hong irrigated their fields, standing face to face on two opposite sides of the pond dug deeply beside the field to get the water in from the irrigation canal. They bent their bodies in cadence to lower a four-gallon bamboo oval-shaped bucket flying down to the pond, their hands holding fast two ropes, tied one to the bucket opening and the other, to its bottom. The bucket getting full of water, Chi and Hong erected, then slightly tilted backwards their bodies, pulling up jerkily the bucket of water and flying it from the pond to the rice field. From the farthest point of the flight, they yanked the bucket back to the pond. By inertia, the water got out of the bucket, pouring down into the field. The round trip of the bucket resembled that of the flying loom shuttle in the rhythm with the successive closing up of Chi’s and Hong’s faces, then, of their bellies, the crossing as well as the locking of their eyes, and the response of her smile to his reminded her of the rhythmic dance of the cranes during their rut period. Extremely happy, Chi felt the fresh air caressing her face, her hands and her naked legs. She enjoyed the smell of the green leaves of the rice plants like the smell of her husband’s breath.

The young couple stopped work when the rice plants had enough water. Hong rolled the ropes around the bucket and sat down beside Chi for a rest under the shade of a jackfruit while she cut glutinous cake. They ate, looking at each other, smiling and seeing the glowing joy in their eyes.

“What are you smiling at?” he asked.

“I’m smiling at it,” she replied.

“It makes you happy, doesn’t it?”

“I don’t know,” she said, turning her head away, flushed with her feelings.

“I can read your eyes.”

“Really?”

“Of course,” he kissed her mouth passionately.

Days and nights flew by peacefully in the ambiance of the intense love between father, mother and child. Strong and smart, their son grew up fast, playing and laughing. He did not bother their parents’ sleep at night.

“When our son will be four years old, I’m going to enroll him at our hamlet kindergarten,” Chi said. “What do you think, honey?”

“You’re right, my darling,” Hong replied. “He’s as smart as his mother.”

“And he’s as handsome as his daddy.” Both laughed heartily.

One late afternoon, in the summer of 1972, Hong hurried home and asked Chi if dinner was ready. He wanted to have dinner right away so that he could get back to the base. He told her to sew a double belt in which she inserted all savings in gold and tie it around the waist.

“Be always calm,” he told her. “Don’t panic in any case. Take our son and mom down in the bunker and sleep there.” North Vietnamese soldiers had concentrated in Trường Sơn Range, South of Bến Hải River. “Be always calm.” He kissed her and his son, wondering what would happen to him and his family.

Chi cooked rice and roasted salted peanut. She put rice in a piece of wet cloth and salted peanut in a plastic bag. She then took her own mother to her home. When the dark covered the whole village, four persons slept soundly in the bunker.

At about 2 a.m. Chi woke up and heard the firing of M-16 guns mixed with distinct sounds of Soviet-made AK-47 guns from all directions, then the explosions of mortars. She knew the village was besieged by enemies. Suddenly, the frightening shouts “Xung phong!”, “Attack!” echoed through out the whole village, followed by the continuous firing of M-16. The shouts died down. Mortar explosions were followed by the lightening gushes of the flying dirt and sand, and the falling of branches on the roof. Chi heard the screams and painful cries from the neighboring houses. She thought someone had been wounded. Her two mothers prayed to Buddha for protection. Chi was anxious for Hong’s safety. Chi got out of the bunker and crawled to open the door. It was getting light. But another round of mortars and cannon bullets hissed overhead and exploded on the other side of the village, then the blasts came nearer and nearer her house. She got down quickly to the bunker. One explosion was very loud very near, sending light, violent gusts of wind and sand to her house, then a crash of a falling tree on her house.

“Mom, I think our jackfruit tree’s been hit and it’s fallen on the roof,” she told her mother-in-law.

“I think so,” she answered, shivering.

The shelling continued. There must be thousands of shells fired into the village. When the shelling came to an end, Chi got out of the bunker, but the tree fallen on the front door blocked it. Right away, shouts of “Xung phong!”, “Attack!” resounded from everywhere. They were followed by the firing of M-16 and .30mm machine guns. The shouts diminished little by little. A deadly silence reigned, no dogs barking, no birds chirping, and no human shadows in the streets. Chi felt restless and anxious, hoping the situation would be like the Tet 1968 Offensive.

It was daylight now, 6:00 by the clock. Chi heard a strange rumbling sound like the rolling sound of tanks. She wondered, VC’s tanks. She did not have time for answer. The rumbling sound came nearer, followed by cannon blasts and AK-47 shots. There was no more M-16 firing. A terrible idea came to her mind, "we’re lost." She did not believe it.

Half-hour later, there were knocks on the door and the call, “Comrades, get out! You’re liberated! Get out!” Chi and two mothers panicked, trembling out of control. Quickly, she got out of the bunker, looked for all documents and pictures of her husband, dug a hole, and buried them all. Chi carrying her son and her two mothers walked out of the gate. A young Vietcong (Vietnamese Communist) soldier clad in a green withered-grass uniform escorted them. Her first sight was on a bloodstained face and chest of a soldier body, lying on his right side, his right leg straight and his left one folded and his two hands on his chest. It seemed that he died when he crawled away.

“Thanh, Hong’s friend, isn’t he?” Chi asked.

“Yes,” Chi’s mother-in-law answered.

“Take care of my son. I’m looking for Hong,” Chi said when the Vietcong soldier went to another house. She ran quickly to the military base. The two mothers followed her. On the base yard Chi saw some local defense soldiers squatting, with both hands tied at their backs by electric wire, heads bent down with haggard countenance.

“Nho, where’s Hong?” Chi shouted to one of the prisoners.

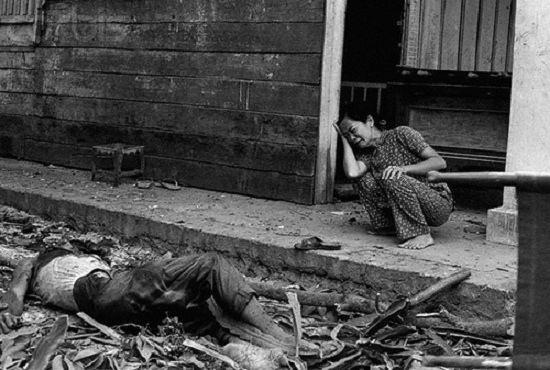

“Shut up, Comrade, or I shoot!” The Vietcong yelled back, pointing his AK-47 at her. Chi wasn’t afraid. However, she stepped back. Nho showed her the direction by moving his face. Chi ran to the indicated direction, followed by her mothers. From afar, she could recognize her husband. Chi ran flying to her dead husband lying, face down, the right arm straight ahead with the fingers gripping the soil, the left arm folded with the hand palm put flat on the ground, possibly having tried to lift his body. Hong’s left leg was suspended in his trench while the right one was on its opening. There was blood all over his back and his head. Chi and Hong’s mother fell on the corpse, embracing it, crying frenziedly, and uttering heart-tearing screams while the child was caressing his father’s hair and face, asking him to get up and kiss him.

“I’m running home to get the cart,” Chi’s mother said, thinking they had to bury his son-in-law quickly in order to find out ways of escape and save her grandson.

Chi’s neighbors and relatives dug the grave while her uncle bathed Hong’s body and put on him a new military uniform and tied it with new fabric. Hong was buried in his garden among grieving cries and mourning tears of his mother, his wife and his mother-in-law.

Knowing that his father would never come back, his son pulling his father’s uniform cried, “Daddy, don’t go! Don’t leave me! Daddy, come back! Come back! Come back!” His screams made others cry louder and louder. But a shout cut short all grieving cries, “Comrades, follow me!” Frightened, the crowd slowly went after him.

All villagers were squatting on the market ground quietly. Then, a tall skinny man with hollow-eyed face and protruded cheeks stepped out, dressed in a black four-pocket shirt, black pants, and a green withered-grass colonial hat. He spoke, his eyes staring straight at the audience with piercing menacing look, “Comrades! You’ve been liberated from the American aggressors and their puppets. Our People’s Army is heroic. Uncle Ho and our Labor Party send you their warm welcome….” Chi did not pay any attention to his speech. But she became attentive when an eighty-year-old, white bearded, gray-haired man spoke in loud voice, “Where’re the Americans? They’re not here. Who did you kill? What did you destroy? Vietnamese people having the same yellow skin, the same red blood as yours. We, people in the South, are richer than you in the North. We don’t need you liberate us…” His wife tried to cover his mouth, but he took her hand off his mouth. “Look at those beautiful big houses you’ve burned, nice furniture, Honda motorcycles, electric network you destroyed. How come the poor liberate the rich?…”

Extremely angry, the political cadre shouted, “You’re a reactionary! Drag him out!” Three VC soldiers pulled him away and the cadre slid away, too. Then there were three shots terrifying all villagers who knew surely he was gone.

“Poor old man!” they murmured sadly.

That night villagers slept on the dirty market ground under Communist soldiers’ watch. It was very black, but not too cold. Nobody could sleep, lying on the cement ground of the market. Chi watched around, noticing the absence of Communist soldiers at about 2 a.m. She sat up and tied her son on her back with a black bath towel. She told her mothers to follow her, crawling like lizards out of the market. They stopped at the village bamboo hedge surrounding her village, watching any human movement. Chi and her mothers snaked through the hedge into the rice field and slowly waded in the muddy water. The fields were dark and silent. The sky was blue, dotted with twinkling stars. Chi heard frog sounds whoop, whoop, whoop, then its shrilled cries. She knew that poor small creature was captured by a snake. Chi tried to place her position and the road. When Chi and her mother reached the road, she saw behind her groups of Lâm Thúy villagers walking hurriedly, carrying bags, helping old women walk, pulling children’s hands, all escaping their burning village. That huge treasure, which villagers had built with hard work, generations after generations, decade after decade, was being burned down in one day. But life, Chi thought, was the most precious thing. She ran slowly, pulling each mother in one hand to Hải Lăng District.

But the Communist terrorists did not leave them safe. Chi heard some starting sounds of mortars and cannons from afar.

“Off the road! Down to the fields!” someone shouted. But too late, bullets and shells exploded along the road. Floods of light illuminated the sky. Plashes of mud and water were flung on the people. Painful cries “Help! Help!” and shrilled calls were around her. Suddenly Chi was thrown forward to the field, lying in the water. She lost her mothers. Peering into the dark, she could not see them. It was too dark after the flashes of light. She called them, but there was no answer. She got up, her hands on her son’s legs and ran, ran across the deserted fields. Cannon shells and mortars flew hissing above her head and exploded, tearing the air curtain like the cutting sound of sharp razor blades. Although exhausted, she kept on running, jumped over mounds of earth, fell down pushing out whoop sound, got up and ran, ran, not paying attention to anything, both hands holding fast her child’s legs. She thought mortars and cannon shells were still hissing overhead and that the explosions would follow. So she told herself she should run as far as she could to avoid being hit. Her son was what she got left and she must save herself to bring him up as her husband and she had wished. She was insensible, noticing nothing around her. Her eyes fixing ahead, she ran, ran as fast as possible although she was out of the cannon range, near Hải Lăng District.

The hot sun was high in the sky. Chi saw soldiers’ shadows in black-dotted green uniforms coming up towards her direction. She believed they were Marines. Coming to the road, she felt safe and slowed down. More Marines were crossing her. Too tired, she came to sit down under the shade of a tree. She untied the towel knots. Surprised, she did not hear her son talk to her. Her son’s body was stained with blood, his eyes vaguely open. She yelled to two Marines passing near her, “Please save my boy, please! Please! He’s wounded.” The Marine, a lieutenant, and his subordinate approached her. Examining the boy, the officer said,

“Your son is still warm, but…”

“No. He’s still alive,” she said painfully. “Please save my boy, please. I just buried my husband, a soldier like you, yesterday morning. I can’t bury my son today. Please save my boy. That’s what I get left now.” The lieutenant did not know how to do, what to say to this grieving mother. His aide suggested, “Call the ambulance with nurses. They can take care of the mother and her son.”

“OK. Do it.”

A jeep with a big Red Cross arrived, carrying two female nurses. The officer said to them, “Please save her son. Her husband, a soldier, died yesterday. She does not want to lose her child.” Chi got onto the jeep and saw that the officer whispered some words to the ear of the nurse. The military ambulance took her to the emergency room in the field hospital. The nurse washed the child’s body, cleaned the wound on his back, made the bandage around his chest, put on him clean clothes and, lay him on a military cot. The nurse told Chi to take a bath. She took her own clothes and gave them to Chi to put on. Lying on the cot with her son, she told him tenderly and softly that she would take him back to the house, that he would go to school according to his father’s wishes, learning a career, and that he would live happily with her. Too tired, she went to sleep soundly.

The following morning, after a long sleep in the safe ambiance, she recovered her senses. She cried, shedding no tears. For she knew now her beloved son had gone with her husband. His legs were cold, his arms cold, his head deadly cold, his eyes closed and his mouth closed, but his back wide open. She called him. But he did not answer. “My god! Everything’s gone!” she uttered. “My husband’s beautiful eyes, his tender words, his caresses, his hot kisses are gone. My son’s innocent words, his beautiful face with sweet smiles, his short life, only four years are gone with his future adolescence. My mothers, all tender affection and deep love, given to me for more than 20 years are lost. My house in which my husband has put in so many years’ work and care, all furniture bought with his savings day in day out are burnt, leaving a heap of smothering ashes, remains from my husband’s father and ancestors’ hard work. My happiness, our young lives, my husband’s love are gone. In the other world, he might be weeping like I am now. All beautiful dreams about my child are gone…gone. My god! What’s left to me? War, charred house, burnt mutilated trees, cold wounded corpses, my lasting sufferings and vivid painful memories of my beloved ones. Who did it? The people of the same skin as mine, of the same DNA as mine, coming from the same ancestors, having the same heroic history, speaking the same language Vietnamese like me. Gone and painful, oh, my God.” |